Gene changes after nerve injury shed light on chronic pain condition

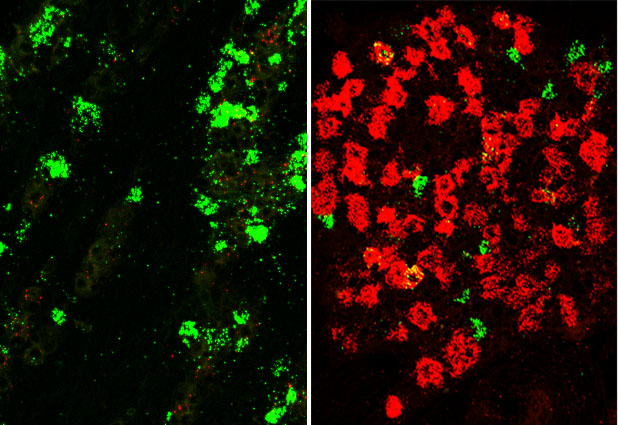

Uninjured trigeminal neurons (left) had higher expression of genes—such as Trpv1 (green)— related to sensory detection and signaling. After injury (right), Trpv1 expression decreased, while expression of genes linked to nerve damage and regeneration—such as Atf3 (red)—increased. | Image courtesy Minh Q. Nguyen.

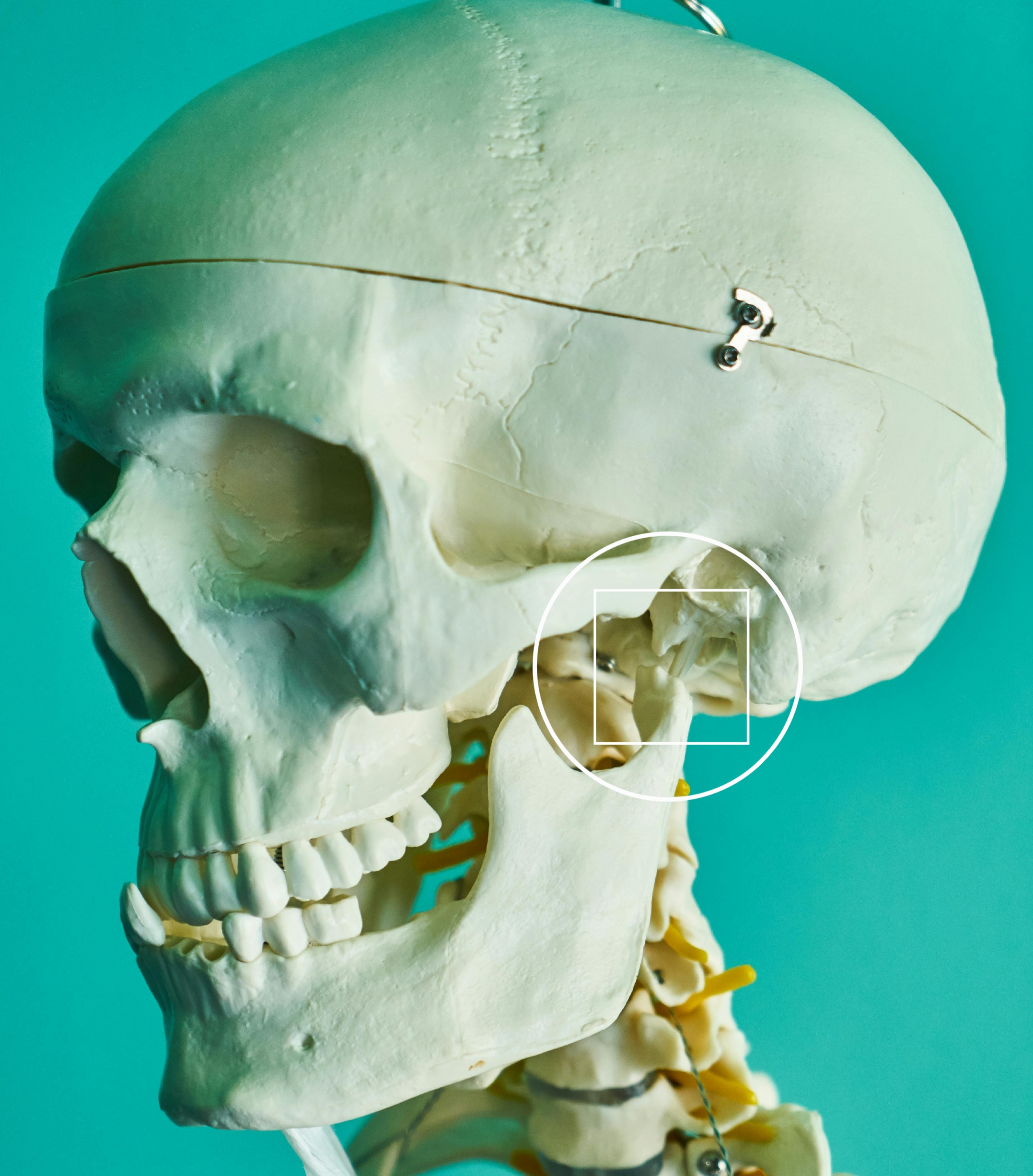

For people with a type of chronic pain called trigeminal neuralgia, touch from everyday activities like face-washing, eating, or tooth-brushing can cause agonizing pain that can be hard to treat. Trigeminal neuralgia is a type of neuropathic pain, which is caused by damaged or irritated nerves. In this case, pain arises from insults to the trigeminal nerve, which carries sensations from the head, face, and oral cavity to the brain. Trigeminal nerves can be injured by a blood vessel pressing on the nerve, surgery, or diseases such as multiple sclerosis. A more complete understanding of the cellular and molecular basis of trigeminal neuralgia could help scientists find treatments that bring better relief to patients.

A recent NIDCR study provides new insight into the origins of the condition. A collaborative team led by NIDCR’s Nicholas Ryba, PhD, and Claire Le Pichon, PhD, of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, found that the gene changes typically seen after neuralgia-inducing damage to mouse trigeminal nerves may not be direct triggers of chronic pain, as scientists previously thought. Instead, the patterns of gene activity, or expression, in mouse trigeminal neurons suggest a role in wound healing after injury. Study results, published in eLife, may help scientists more precisely pinpoint targets for therapy.

Ryba’s team used a recently developed method called single-nucleus-based RNA sequencing, which enables scientists to measure gene expression of single neurons. They found, consistent with earlier studies, that severe, neuralgia-inducing trigeminal nerve injury rapidly leads to a pattern of gene expression distinct from that of uninjured neurons. Scientists previously thought these damage-induced gene changes directly drove neuropathic pain. However, the NIH group was surprised to find that even minor injuries that don’t produce neuralgia led to similar gene changes in trigeminal neurons. These shifts included increased expression of genes with roles in neuron growth and tissue remodeling after injury and decreased expression of genes involved in neuron signaling and sensation detection.

“Rather than directly driving trigeminal neuralgia, the gene expression changes seem to indicate transition to a wound-healing state that allows injured nerves to reconnect and maintains sensation during and after many types of injury,” says first author Minh Q. Nguyen, PhD.

To explore this possibility, the scientists used CRISPR editing to genetically label mouse neurons and track them for 21 days after nerve injury. Consistent with the team’s predictions, the neurons gradually returned to a non-injured gene expression state even after profound injury.

“Our observations support the view that trigeminal neuralgia may not be directly propelled by injury-related gene expression in neurons that initially detect pain, but rather by changes higher up in parts of the brain that receive and process these signals,” says Nguyen. “The results may also explain why neuropathic pain is a rare, but significant, complication of many types of relatively minor surgery, and could help point us toward more effective therapies.”

Reference

Stereotyped transcriptomic transformation of somatosensory neurons in response to injury. Nguyen MQ, Le Pichon CE, Ryba N. Elife. 2019 Oct 8;8. pii: e49679. doi: 10.7554/eLife.49679. PMID: 31592768.

NIH Support: In addition to NIDCR, support from this study came from the intramural program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and a DDIR Innovation Award. Launched in 2017, the DDIR Innovation Awards program provides seed money to stimulate innovative, high-impact research and to foster collaborations.

ARTICLE SOURCE: NIH’s National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research

Leave a Reply